C.H. Spurgeon: Pastor-Theologian (Part 1)

Charles Haddon Spurgeon was born June 19, 1834 in the Essex County village of Kelvedon. His parents sent him to live with his paternal grandparents in Stambourne fourteen months later. He remained in their care for the next five years before rejoining his parents in Colchester. He spoke fondly of his grandparents whom he visited often in childhood. Their home was an inimitable setting for the curious young Spurgeon to spend his early years.[1] His grandfather, James, was a Congregational minister steeped in English Puritanism.[2] His study contained the works of many Puritan greats in which the young Charles was deeply interested.[3] Indeed, it would be his encounter with the Puritans of his grandfather’s library to which he would return as the remedy for the theological ills of London.

Out of that darkened room I fetched those old authors when I was yet a youth, and never was I happier than when I was in their company. Out of the present contempt into which Puritanism has fallen, many brave hearts and true will fetch it, by the help of God, ere many years have passed. Those who have daubed up the windows will yet be surprised to see Heaven’s light beaming on the old truth, and then breaking forth from it to their own confusion.[4]

Spurgeon would not only return to his puritanical roots later in ministry, but in the very year that the Downgrade Controversy commenced, he would be reminded of those early days and his fearless public theology. He didn’t have the stomach for error and sin, even as a child. On a visit to Stambourne in 1887 he was told a story from his childhood wherein he confronted a member of his grandfather’s congregation engaging in the abuse of alcohol and worldly amusements. The young Spurgeon stormed into the pub and addressed the man, “What doest thou here, Elijah? Sitting with the ungodly; and you a member of a church and breaking your pastor’s heart. I’m ashamed of you!”[5] The man put down his beer, ran from the pub, and fell down in a heap of repentance. He came to Spurgeon’s grandfather and asked for his forgiveness as well, saying, “I’ll never grieve you any more, my dear pastor.”[6] The young Charles was ferociously on his way toward a life of public ministry.

Stambourne House

Others noticed the young Charles and the potential gospel affect he could generate later in life. While visiting Stambourne at the age of ten, he met Richard Knill of the London Missionary Society. Knill spent several days with the Spurgeons, explaining the gospel to young Charles and praying with him. Knill announced to the entire family, “This child will one day preach the gospel, and he will preach it to great multitudes.”[7] Reflecting on that earlier experience, Spurgeon remarked, “Did the words of Mr. Knill help to bring about their own fulfillment? I think so. I believed them and looked forward to the time when I should preach the word.”[8]

Parental Influence

In 1840 Charles moved back home with his parents. Both were ardent Christians, intent on bringing him up in the nurture and admonition of the Lord.[9] His father, John (1810-1902) was a bi-vocational pastor, serving a Congregational church in Tollesbury while employed as a clerk in a coal merchant’s office. His mother managed the household comprised of Charles and his three siblings (two sisters and a brother), with fastidious gospel focus.

Yet I cannot tell how much I owe to the solemn words of my good mother. It was the custom on Sunday evenings, while we were yet children, for her to stay at home with us, and then we sat round the table, and read verse by verse, and she explained the Scripture to us. After that was done, then came the time of pleading; there was a little piece of Alleine’s Alarm, or of Baxter’s Call to the Unconverted, and this was read with pointed observations made to each of us as we sat round the table; and the question was asked, how long would it be before we would think about our state, how long before we would seek the Lord. Then came a mother’s prayer… “Now, Lord, if my children go on in their sins, it will not be from ignorance that they perish, and my soul must bear a swift witness against them at the day of judgment if they lay not hold of Christ.”[10]

Spurgeon would speak often of his indebtedness to his upbringing under the pastoral hand of his grandfather and father as well as the tender pious instruction of his mother.

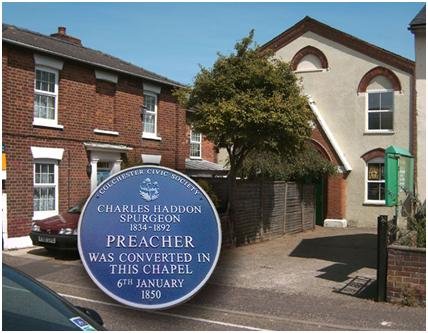

Conversion

On January 6, 1850, Charles Spurgeon was born again. School had been dismissed early because of an outbreak of fever. A snowstorm kept him from attending church with his family in Tolesbury, so he found his way to a Primitive Methodist Chapel. He had long been wrestling with his own sinfulness and need for Christ, returning often to the books his mother read him on Sunday evenings only to intensify the knowledge of his need for Christ. In the Methodist chapel, there were but 12-15 people in attendance.

Methodist Chapel

The minister was snowed in, so a layman stood to preach the message. His text was Isaiah 45:22, “Look unto me and be saved, all the ends of the earth; for I am God and there is none else.” Spurgeon recounts the sermon as less than impressive, but deeply effective. The preacher looked directly at Spurgeon to speak, “Young man, you look very miserable and you will always be miserable…if you don’t obey my text; but if you obey now, this moment you will be saved.” He continued, “Young man, look to Jesus Christ. Look! Look! Look! You have nothin’ to do but to look and live.”[11] Spurgeon responded to the gospel message in repentance and faith.

I saw at once the way of salvation. There and then the cloud was gone, the darkness had rolled away, and that moment I saw the sun; and I could have risen that instant and sung with the most enthusiastic of them, of the precious blood of Christ and the simple faith which looks alone to him.[12]

Spurgeon would reference this event frequently, recalling the grace of God to him in the back of a Methodist chapel, saving him from sin. “That happy day, when I found the Savior, and learned to cling to his dear feet was a day never to be forgotten by me.”[13] He was baptized on May third of that year and in his diary wrote, “I vow to glory alone in Jesus and his cross, and to spend my life in the extension of his cause, in whatsoever way he pleases.”[14]

Notes

[1] Spurgeon described his grandparents’ home in great detail. “This parsonage is two hundred years old, and consists of a stout framework of wood, filled in with lath and plaster. Strong timbers of oak, some of them roughly hewn, combined with oaken rathers and laths, give shape to the roof, which is overlaid with thickly-set tiles…” C. H. Spurgeon and Benjamin. Beddow, Memories of Stambourne. Stencillings by B. Beddow ... With Personal Remarks, Recollections, and Reflections, by C.H. Spurgeon. (London: Passmore & Alabaster, 1892), 26. In one quaint story, he described a wooden rocking horse as “the only horse I ever enjoyed riding. Living animals are too eccentric in their movements, and the law of gravitation usually draws me from my seat upon them to a lower level; therefore, I am not an inveterate lover of horseback. I can, however, testify of my Stambourne steed, that it was a horse on which even a member of Parliament might have retained his seat.” C. H. Spurgeon. C. H. Spurgeon Autobiography: Volume I: The Early Years, 1834-1859 (Carlisle, PA: The Banner of Truth Trust, 1976), 4.

[2] [He] “seemed to live as one of the last representatives of the Old Dissent. In all his tastes, manners, and aspirations, the veteran belonged to a generation which had long since passed away.” He spoke of the elder Spurgeon’s congregation as “a rare instance of Puritan fervor burning on through two centuries.” Spurgeon, Autobiography, 2.

[3] “Here I first struck up acquaintance with the martyrs, and especially with ‘Old Bonner,’ who burned with them; next, with Bunyan and his ‘Pilgrim’; and further on, with the great masters of Scriptural theology, with whom no moderns are worthy to be named in the same day.” Ibid., 11.

[4] Spurgeon, Autobiography, 11. Spurgeon’s description of “daubing up the windows,” and reading in a “darkened room” refers to the infamous “window tax” which sought to estimate the wealth of the homeowner based on the number of windows. To get around this tax, residents would paint over their windows, blacking them out. Hence, Spurgeon referred to the library at Stambourne as a “dark den — but it contained books, and this made it a gold mine to me” Ibid., 11.

[5] Ibid., 12.

[6] Ibid., 12.

[7] Ibid., 27.

[8] Spurgeon, Autobiography, Vol. 1, 28.

[9] “I was privileged with godly parents, watched with jealous eyes, scarcely ever permitted to mingle with questionable associates, warned not to listen to anything profane or licentious, and taught the way of God from my youth up.” Ibid., 43.

[10] Ibid., 44.

[11] Spurgeon, Autobiography, Vol. 1, 88.

[12] Ibid., 88.

[13] Ibid., 89.

[14] Ibid., 131.